A TALE OF TWO SPRINGS

Five years ago the Northeast saw its earliest spring on record; will this year be the latest?

John O’Keefe, field phenologist at the Harvard Forest and I went out on John’s first tree survey of the new year today. While it was April 1 – his traditional first walk of the season – we were not intending it to be an April Fool’s gag. But you could have thought so, as we post-holed through the snow. There was surely no spring to be had! Not in the trees, not in the shrubs, the birds, or the animals. Just a bit of open water here and there, a very few patches bare ground, and the streams were running. Other than that, it sure looked a lot like…winter.

The first bud test of the new year. We saw virtually no signs of spring yet at the Harvard Forest on our first phenology walk of the year. John’s records show at this time in 2010, there was no snow at all, frogs were singing, and red maples were in flower. Photo by Doug MacDonald

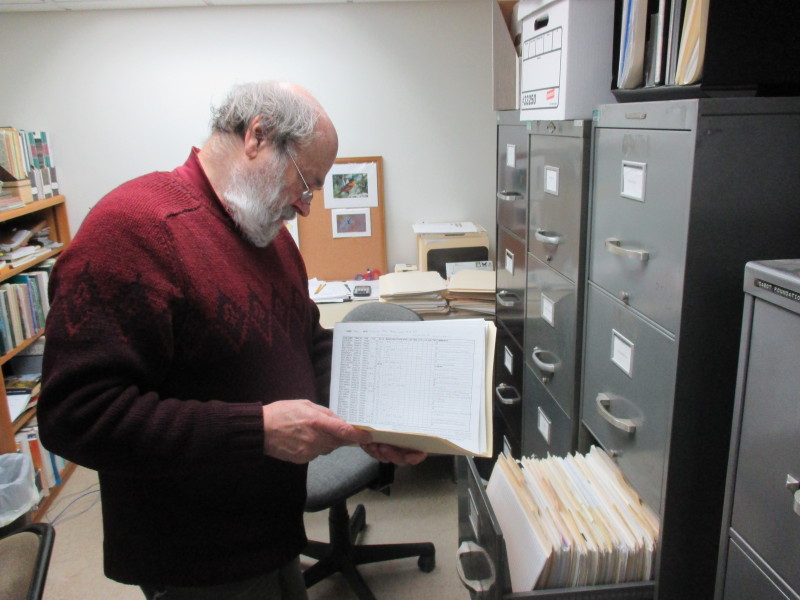

I packed a ruler along and we measured at least 10 inches of snow on the ground in most places. The Hemlock Hollow, the vernal pool we watch where the wood frogs first sing, was still sealed over with ice. The day was sunny but cold, in the high thirties. And the trees – well. John has been surveying the same 50 trees for 25 years to track their seasonal progression. The trees’ first green up marks the beginning of the photosynthetic cycle for the year – and he closely notes the changes in the trees, from first swelling and cracking of buds to leaf emergence, growth, color and drop.

A squirrel scooting over the snow is photographed by the wildlife camera set up by the big oak I am studying at the Harvard Forest. This is a tough time of year for animals running out of food stores while snow is still deep on the ground.

John makes his observations in collaboration with the Andrew Richardson, associate professor at Harvard University, who uses the seasonal progression of the canopy as a marker of the effects of climate change on the forest. Over the past 25 years, O’Keefe has noted a shift toward earlier on average springs, later falls, and winter squeezed on both ends because of global warming.

But this year’s spring is so late, and last year’s too, that the average earlier spring trend could even be reversed, and will surely be dampened, John said. Because fall has been consistently later, the overall longer growing seasons of recent years will still likely still hold true.

We checked for any sign of spring in the trees and saw just maybe a little slight perhaps sort of tiny bit of swelling on the buds of a few black cherry trees – always among the first to transition. Nothing else had budged a bit. The snow shone brilliantly in the spring sun, but the sun’s higher position in the sky was about it for seasonal change.

We came across a few smaller sample trees buried nearly to their flagging in snow. I nearly lost the ruler while making a few measurements, the snow banks were so deep. At least the streams were thawed and moving.

Once back at Shaler Hall, we were curious to see John’s data from the earliest spring in his 25 years of record keeping, walking the same 2.5 mile loop and examining the same trees on April 1, 2010. We knocked the snow off of our boots and went down to his office to pull the data.

What a shocker. April 1, 2010 was booming. The wood frogs were singing at the Hemlock Hollow. The skunk cabbage was “still blooming.” The red maple flowers were open. The striped maple’s bud scales were split, and witch hazel buds were softening. The was no ice on the Hemlock Hollow, no snow anywhere, and red oak acorns on the wagon road were germinating. The mayflower was up, and it was nearly 60 degrees. It had been warm for weeks, with late February and March consistently warmer than normal.

It was interesting to pull John’s record from the same day five years ago and see just how different the earliest spring looked from the same day in what may turn out to be the latest.

This is what scientists mean when they talk about inter-annual variability. Big swings, from one year to the next, as global change rattles the seasonal works. Who knows what next year will bring? These past five years tell us this much: anything could happen.

Any spring up there? John uses binoculars to look for any signs of swelling on the buds of the big red oak I am studying at the Harvard Forest. It’s going to be a while. The camera beaming photos every half hour during daylight hours of the big oak to the Harvard Forest home page is visible on its mount in the snow, to the right of the tree.

Leave a Reply