AND THE WINNER IS: RED OAK

May 7, 2015

In a Googled world, The Harvard Forest is the land of the long view, the deep dive, a place where researchers look up close at the landscape and its history, to see what the trees can teach. So it is that Audrey Barker Plotkin and I recently went out to take a look at what she had learned at Walter Lyford’s plot.

Audrey Barker Plotkin locates the red maple, left, and red oak, right, depicted on Lyford’s hand-drawn map. Unique, long term data sets are a hallmark of the Harvard Forest’s scholarship.

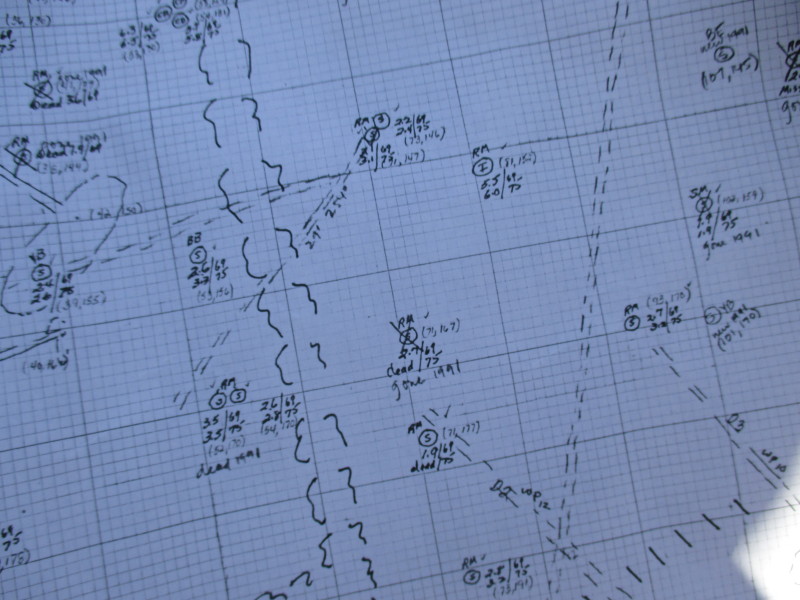

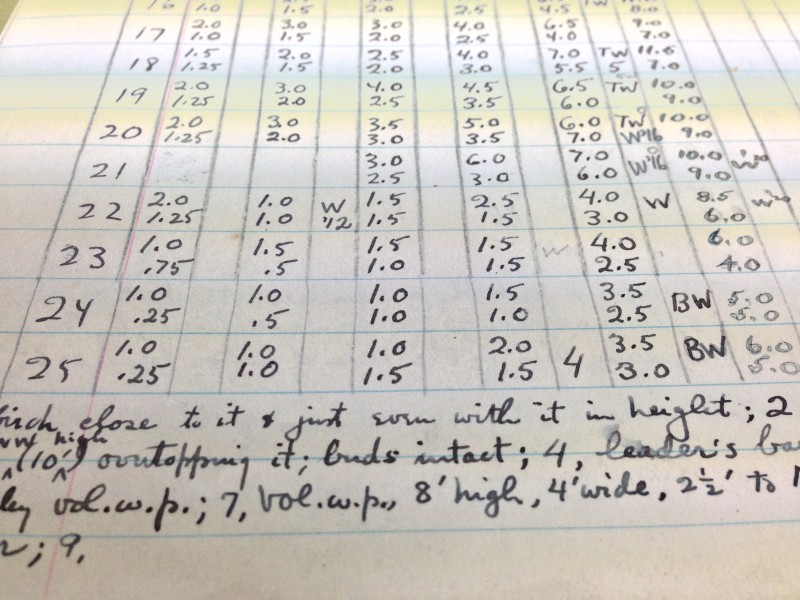

Lyford was a meticulous soil scientist at the Harvard Forest, a 3,700 acre research forest in Petersham, MA and a department of Harvard University. He established a permanent 7 acre plot at the Harvard Forest in 1969, where he measured and located every tree over two inches in diameter on a hand-drawn map — 6,000 trees in all. This beautiful, large-scale map is preserved at the Harvard Forest Archives today. It includes every feature on the forest floor in the plot: live and dead trees, stonewalls, boulders, and more.

Barker Plotkin, research manager at the Harvard Forest and her collaborators have been considering the 42 years of monitoring data accrued by now in five surveys of the plot, including the most recent, in 2011. What they found was new relevance in old data, because of the point of comparison Lyford’s baseline provides in a changing world. Since the plot was first laid out in 1969 much has happened – including the acceleration of climate change, and atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide causing it. It’s a change you can see in the trees.

In a Google world Walter Lyford’s hand-drawn map meticulously noting the features of his study plot is a treasure of detailed, place-specific information.

Barker Plotkin and Kate Eisen of Cornell University – who did her work as part of the undergraduate research program in ecology at the Harvard Forest — published their results in the Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society today. The paper documents their analysis of a 2011 resurvey of the 6,000 trees in the Lyford plot, showing the trees in this mostly 110-year old stand are still growing – especially red oak.

From 1969 to 2011, red oak increased its dominance in this grove to clock nearly 70 percent of the total tree biomass. Meanwhile red maple receded to a lesser presence, as red oak asserted itself over the maple canopy.

Barker Plotkin checks Lyford’s map to locate two individual trees, using the handy desk of a stone wall — also on the map, of course.

On our walk, Barker Plotkin and I used a Xeroxed portion of Lyford’s map to find a classic example of this dynamic. She unrolled the map on a boulder (also on the map) and crooked her head back to point out a pair of trees, one a big red oak, and the other a red maple tucked under its canopy.

“If you want to see how great oak is, this is a pretty good place,” she said. Both trees had been measured and mapped in Lyford’s original survey. That enabled Barker Plotkin to see the maple had grown half as much as the oak over the 40-year period. And the oak were still surging ahead.

That’s the small, two-tree picture, but the value of it is that these two trees, watched over time, tell a planetary story. The tale of two reds – red maple and red oak – revealed by the long term research plot is that in the absence of some sort of major wipe out storm or other disturbance, red oak will continue to increase in size, and the stand will keep packing away the carbon it pulls out of the atmosphere for at least another century.

Red oak is the workhorse of the forest: its biomass more than doubled in the intervening years since Lyford’s initial mapping – compared with a 48 percent increase in all the other species. Part of the surprise in the data was how strongly red oak is still growing, even past its 100th year. It could even keep right on going, barring as storm or other major disturbance, maintaining their dominance and packing away carbon into their 200th year and beyond.

These oaks are literally eating into the carbon dioxide emissions people are putting into the atmosphere. Trees use carbon dioxide for their food source, to create sugar using the energy of the sun in the process of photosynthesis. Every atom of carbon a tree takes out of the air and tucks away in the form of wood, leaves or roots is that little bit less carbon in the atmosphere, trapping heat energy that’s changing the seasons, and the climate.

But just how is it that red oak dominates its grove? Partly, it’s red oak’s style. In a forest, red oak grows in a straight shot to the canopy then spreads a large crown with big strong branches. Red maple takes a more bulbous, contained form. The red oak simply overshadows it – literally. Researchers in the Richardson Lab at Harvard University have also found red oak is honing its performance in response to higher carbon dioxide levels and longer growing seasons caused by global warming. Red oak is increasing both its water use efficiency, and growth.

Audrey Barker Plotkin heads out to the Lyford plot at the Harvard Forest, with a photocopied section of Lyford’s map.

I am studying a big oak at the Harvard Forest that’s a textbook example of the red oaks in the Lyford plot. While not in the same part of the forest, its life story is the same: it sprouted in what was a pasture cleared by Europeans from the original forest. The pasture was abandoned in about 1840, and then grew in to white pine, cut intensively in the late 1890s. The oak I study today is part of the mixed-hardwood forest that came in after the pine was slicked off around 1900. It’s the third growth forest that comprises most of the Harvard Forest today – and red oak is its dominant tree.

Red oak’s witness and role as the industrial economy roared to life, and people left these pastures and farmlands to grow back to woods is the story I tell in my forthcoming book, Witness Tree. It’s a story about not just one red oak, but our relationship with nature, and the role of trees in our changing world.

THE FINE ART OF PAYING ATTENTION

May 2, 2015

JOHN HANSON MITCHELL is a master of the fine art and deep pleasure of paying attention. Author of Ceremonial Time, Fifteen Thousand Years on One Square Mile, a landmark in American natural history writing, among other books, Mitchell also was the editor of Sanctuary, the splendid magazine published by Mass Audubon for 34 years until it was (to me, inexplicably) discontinued last year. You can read a collection of his natural history essays from Sanctuary here.

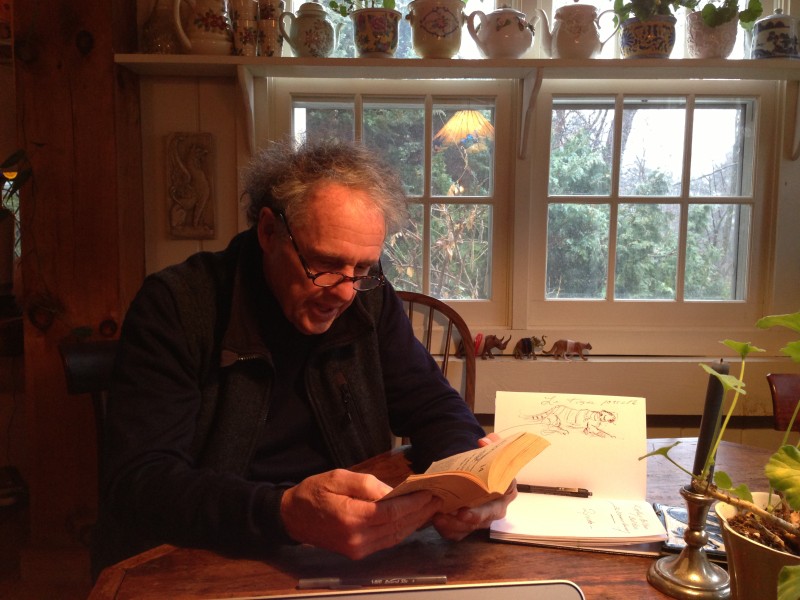

I asked author John Hanson Mitchell if we had the right to do what we are doing to the planet with climate change and he answered “…the judges are the animals.” Note the animal sketched in his journal, and the animals on the window sill at his home.

When I began work on my own book, Witness Tree, last year about the human and natural history of a single 100-year-old red oak at the Harvard Forest, I knew Ceremonial Time, a classic in the genre of deep observation of one place – think Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac, or Henry Beston’s The Outermost House — was a must-read for me. It had been in my house, and my husband’s before mine, for many years. I tucked the slim paperback with its venerable, yellowed, crackly pages amid the books we packed when I headed to the Forest last fall to begin a year’s sabbatical year away from my job as a reporter at the Seattle Times, to write the book while a Bullard Fellow in forest research funded by Harvard University and based at the forest.

John Hanson Mitchell’s writing studio, one of several out buildings on his property he has made into personal havens for work and observation.

In his book, Mitchell explores one square mile of America – its life, legends, and 15,000 years of history in what he calls Scratch Flat, an ordinary bit of New England woods and pasture, and his home for more than 30 years. It is one of those books in which nothing happens, and everything happens, and is the story of no place in particular, and therefore everyone’s place – it is about not the grand wildernesses and remote, mystic redoubts of John Muir, but the quotidian places where most of life happens. The places we call home.

So it wasn’t long after I arrived here that I looked Mitchell up, and found him at his home, still in Scratch Flat, on a wet winter day.

What a deeply nested home: the main house was full in an uncluttered way of personal treasures of every sort. But it got better, as Mitchell showed me the collection of outbuildings he has created over the years, one for a writing studio, another a cabin retreat, a third a gazebo for sitting in his carefully tended garden. It is here that Mitchell lives the practice of phenology – the observation of the seasonal progression of nature. Phenology has been rediscovered by mainstream scientists as a way to document the affect of climate change on the land, as seasons change in a warming world. But for most of us, phenology is today what it has always been for people, everywhere: the art and pleasure of paying attention.

Into the garden, his refuge and place of contemplation. Mitchell uses only hand tools — in part to be able to hear the birds as he works.

Mitchell visits the landscapes of Beaver Brook near Littleton, MA, a.k.a. Scratch Flat daily, just as he has for more than 30 years. “It is very peaceful, you can hear the highway on some days, but there are these empty spots here on Scratch Flat…and I go down there and it is total peace. Winter wrens, the pale winter sun, that smoky hazy day like today, it is beautiful with the shades of colors like tapestry. You see more life in the winter, you can see who has been there, fishers and coyotes and deer.”

Watching the progression of the seasons is second nature to him: “It’s how I tell time,” Mitchell said.

The garden is part of how and where he witnesses climate change, in both its day-to-day reality, as seasons change – and how he copes with the fact of it. “You forge on in the fact of it,” Mitchell said. “This thing of a billion other possible planets, that is good news. Maybe it doesn’t matter. The sun is going to burn out. In the history of the universe we are a pretty short-lived phenomenon, the human race doesn’t even register.

“We are pretty homocentric – is that a word?” Mitchell says, looking out the window to his garden. “I just carry on I guess, the garden is getting to be a metaphor for me. I take the long view. The Earth is going to endure.

“We’ve got, what, 5 billion people, a huge percentage of whom are not educated to these matters here in the United States which is supposedly educated. For Christ sake you have people who don’t believe in evolution, what is it, 41 percent of the population? What hope is there for such a people. And you can quote me on that.” Actually, it’s more than 7 billion people, including 42 percent of 318 million Americans who don’t believe in evolution, according to a 2015 Gallup poll.

Both sanctuary and observation post, his garden is where Mitchell watches our changing world unfold. He works strictly by hand, clearing, tending, pruning and shaping the thousands of ornamental plants he has planted at his property over more than 30 years. “The garden is a place, but it’s also a metaphor. It’s a sanctuary here for me.

“This takes work. I like the work. That is the main existential statement. It is hand work, I don’t use machines. I hate machines. I hate chain saws. I hate leaf blowers.”

Mitchell came to visit the Harvard Forest this week to speak at a conference, and so I took him out to meet the Witness Tree I am writing about. He put hand to its gnarly bark, tipped his head back to enjoy the canopy’s structure, asked about the life of the soil, the doings of the soldier beetles, did I know about them? For to Mitchell, everyone should know about everything in their little patch of the world around them. And for those who don’t pay attention to the great gyre of their small Scratch Flat, wherever it is, well. They are missing out.

“They are missing the scent of fresh cut hay, frog calls,” Mitchell said. “They are missing everything, 100,000 year’s of contact with nature, with the world, the real world. The arrival and departure of birds. I really don’t need a calendar any more, I am really conscious of the seasons. But it is changing, shifting, I have watched the gardens here for 30 years, and we used to get the first frost September 18 on the Equinox, a light frost, then we would get a killer on the 10th of October.

Looking up to the canopy of the Witness Tree. Just as John O’Keefe, field phenologist at the Harvard Forest has seen the timing of seasons change at the Harvard Forest over the past 25 years of his observations, Mitchell notes later killing frosts in the fall, and on average, milder winters during his 30 years of observations at Scratch Flat.

“Now the light frost is in October and the killer is in November, and that is pretty standard for the last 15 years. We used to be a (USDA Plant Hardiness) Zone 4, now it’s 5 and we are pushing 6. I can grow plants here I couldn’t grow 20 years ago. I am growing a tree native to the Smoky Mountains. I should try crepe myrtle.”

And so as the great world spins, and another spring comes, Mitchell is back out in the garden, to work with his hand tools. “I love to scythe, you are on your own time, you want to listen to the birds, and with hand tools, you can hear them. I smell the grass, I just stop a lot and just stare into space.”

I listen, then have to ask him. For someone obviously so appreciative of nature’s wonder, what about climate change? Do we have the right to do what we are doing to the planet? He stops and thinks about that. Then answers me:

“If the animals could vote, they would say, we have no right. If they could put us on trial they would say we had no right to do what we did, that we are guilty.

“Do we have the right? Who’s to say, who is the judge on that. Right or wrong. I don’t know. I don’t know the answer to that, because the judges are the animals.”

Author John Hanson Mitchell at home in Littleton, MA, a.k.a. Scratch Flat, the landscape he memorialized in his book Ceremonial Time.

PHENOLOGY: ON THE HUNT FOR SPRING AT THE HARVARD FOREST

April 30, 2015

The tree line is flushed with red maples in bloom; the black cherry is in leaf, and the first ferns and mayflower are making a brave start: spring has arrived at the Harvard Forest.

The frogs got it started, first the woodies with their weird quacking call, and now the peepers are positively deafening. Last night under a waxing moon I went out into the forest with friends after dinner to follow the peepers’ calls to a pond in the woods. We stood in awe as the season’s first moths cruised the warm night, the moon reflected off the water, and the peepers sang their little hearts out. No bigger than the first joint of a finger and perfectly camouflaged, even with our flashlights we could not see what we heard all around us. So we just enjoyed their night music, eventually returning to Community House here at the Harvard Forest where we all live. The moonlight spilled silver through the trees onto our woodland path.

It was a magical coda to one of my favorite things: a day spent in the woods. I was out all afternoon doing the tree survey that John O’Keefe, field phenologist at the Harvard Forest, usually completes in about three hours. John has been doing this survey for 25 years and reads the woods as rapidly as a newspaper. I understood with new appreciation the complexity of phenology: the practice of observing and recording the seasonal progression of nature, as I tried doing his job even for a day.

Making notes on the phenology of the Harvard Forest tree canopy. Documenting the seasonal progression of buds and leaves on the trees and woodland shrubs is an excellent way to discern the effects of climate change on forest ecosystems.

I have been at the Harvard Forest since September on a Bullard Fellowship in forest research, to work with researchers using tree canopy phenology to observe the effects of climate change on the timing of the seasons, and the forest’s ecology. Scientists in the Richardson Lab at Harvard University do this in a number of ways. John and researcher Steve Klosterman monitor the grand procession of the seasons week by week, watching for leaf emergence, color, and drop in spring and fall. John does his survey on foot, and Klosterman deploys a drone to photograph the canopy on weekly flights.

Red elderberry were the first plant to leaf out at the forest, and now their flower buds are starting to color.

Andrew Richardson, associate professor at Harvard University meanwhile keeps a constant electronic vigil on the canopy, with web cams he has installed on towers in the forest.

With John away this week it was my turn to do the ground survey, tracking the 75 trees he monitors in spring. It’s actually quite demanding. Are those buds slightly swollen, moderately swollen, or broken and in first leaf? What about the flowers on the maples and the shad bush – are they open? This all sounds easier than it is when the tree canopy is 60 feet up. But what a pleasure, to slow down enough to actually look at a whole tree, in detail, and watch spring unfold tiny change by change. A privilege, actually, in our rushed and digital world. So yesterday I spent most of the day craning my neck at tree branches, and pulling them in close to study their buds.

A spring azure butterfly visits my boot. Common in the New England woods from late April through September, they are anything but common in their lovely appearance.

Everywhere, there were signs of spring: the first emerging ferns raised their fuzzy, tightly coiled heads through last year’s leaf litter. Mayflower, one of the first spring ephemeral wildflowers, was pushing brave spears up through the duff. The skunk cabbage unfurled big, glossy leaves with a tight hooded maroon speckled flower at their base. The striped maple had cracked their buds and were pushing out tender new leaves.

The red elderberry flowers were just starting to color, and I was aware of a new busyness on the forest floor, as the ants and spiders got to work in earnest. I saw my first mosquito, but the black flies aren’t here…yet.

I was visited by a spring azure butterfly, which basked on my boot. This tiny delicate creature lives up to its poetic name, with a sky blue color and delicate wing span under one inch. Slender and lovely, it is a common butterfly in New England, but a wonder on the wing, a flutter of lavender blue after a long snowy winter of white and grey. Spring azures are commonly seen from late April through September – making my April 29 visitor right on time.

I was delighted to see the woods coming to life all around the big oak I am studying at the Harvard Forest. Entering its 100th spring, I am writing a book, Witness Tree, under contract with Bloomsbury Publishing, about this tree’s century of human and natural history, and what they reveal about our changing relationship with nature and its consequences. With the help of researchers at the Richardson Lab, including John O’Keefe, I am also studying the phenology of the forest canopy and how it reveals changes in the physiology of this tree and others because of climate change.

The first ferns and mayflower emerge at the foot of the big oak I am observing at the Harvard Forest for my book Witness Tree.

A branch I collected from the big red oak and stuck in a vase weeks ago at my house has finally burst into its first leaves. Try this: it’s a great way to look at the emergence of leaves up close, and appreciate the incredible changes as they unfurl. At first the leaves on the big oak are no longer than my fingernail, yet their oak shape is fully defined. I look forward to watching them grow up close. But as I surveyed the big oak’s branches in the field yesterday, it looked to me like it could still be weeks before it comes into leaf. You can watch spring unfurl at the forest for yourself in real time on Harvard Forest web cams, including one under the Witness Tree.

There is so much change underway, every day. Phenology is the practice of tracking of those changes, with a whole new relevance in the era of global climate change.

How lovely to see the first spring ephemeral wildflowers start to come up amid the cracked shells of the acorns that carried the animals through last winter.

THE SOUND OF SPRING

April 17, 2015

The wood frogs are calling. I hear their maniacal quacking everywhere now in the woods. Not the high trill of a spring peepers, the sound of the wood frog, Rana sylvatica, is somewhere between the sound of a duck and, well, nothing I have quite ever heard.

A wood frog floating in a vernal pool this afternoon by the big oak I am studying at the Harvard Forest. The woods are suddenly alive with their calls. Oaks and red maples are reflected in the clear, cold water which is just a few inches deep.

After making it through the winter, freezing nearly solid tucked just under the leaf litter and several feet of snow, these are the first frogs to head to their breeding ponds. John O’Keefe and I were out sampling trees today, to look for the first signs of spring. Then I heard it: the unmistakable happy racket of wood frogs. We finished our survey and I made a mental note to come back later and follow that sound.

This vernal pool is alive with frogs and bugs. What a dreamy, ephemeral beauty. It will be gone by summer as the trees leaf out, drawing in this water and transpiring it through their leaves as they photosynthesize, making sugar from sun.

Later in the afternoon as the temperatures soared into the sixties under an azure sky, I booted it across the greening pasture to the big oak I am studying at the Harvard Forest, and started listening. Not 400 feet from the tree, a beautiful vernal pool came into view. An ephemeral wetland, it was just inches deep, really just a wet spot in the woods. Amid a delicious tangle of rotted stumps, mossy rocks, and trees, this clear, cold pool, with ice still clinging to its edges, was alive with wood frogs.

Wood frogs are the first frogs to call in spring, heading to their breeding ponds still rimmed with ice.

At the first sense of my presence they silenced. So I sat myself down on a soft cushion of leaves and moss and let myself drift off into a nap, the warm spring sun on my face, waiting for the frogs to reassert themselves. It wasn’t long before they stirred, and so did I. How secretively they slid up from the leaves layered on the bottom of the pool, poking their noses out of the water, their eyes abulge at the still, glassy surface!

What all the fuss is about. These eggs will hatch out to tadpoles in as few as ten days. They will metamorphose to forest-dwelling froglets by the time the pool dries up this summer.

A fat beetle swam by under the water; delicate water bugs silked along the pool’s surface. So much life, and I never would have even known this pool was here, were it not for the sound of the frogs. The pool will dry by summer. That makes it a perfect habitat for the frogs to rear their young, because the pool cannot support fish, which would gobble the tadpoles. Instead, they will grow on to hopping froglets in time to take to the woods before the pool dries.

Everywhere in the woods now is the sound of water. The snow has melted as dramatically as it arrived. A few banks remain in the coolest shadiest spots, some 8 inches deep. But mostly, the forest is back, and coming alive with spring. A yellow warbler serenaded us as O’Keefe and I walked this morning, and a morning cloak butterfly flew and basked in the soft spring sun. The light in the forest is so special now, with the sun climbing higher by the day, and pouring through the trees to the understory with no leaves yet to shade it. We saw our first wildflower setting bud today, a Canada mayflower.

Everywhere in the forest is the sound of water as the snow melts out at last, feeding brooks, springs, pools and ponds.

We looked hard at the trees John surveys — black cherry, quaking aspen, ash, yellow and black birch, beech, striped maple, paper birch, red and black oak, red maple and sugar maple. We studied the woodland shrubs: witch hazel, shad bush, and hawthorne. But while the striped maple had cracked its buds, and red maple showed swelling buds, it looks like it will still be a couple more weeks before the first leaves. The only bud I saw actually open today was a red elderberry, big and fat, and revealing the green nub of its flower to come.

John looks for opening buds as spring sun pours through the bare trees to the understory, which will not receive as much sun the rest of the year as it does right now. This feast of warmth and light will soon bring wildflowers, basking in their brief window of sun before the leaves emerge on the trees.

Insects were in the air, the first bees were about, and for weeks now there have been more birds every day; I’m awakened every morning now by the drumming of flickers and wood peckers. I keep my window wide open to hear the frogs at night, and spring birds at first light.

WARM PLUS COLD EQUALS FOG

April 10, 2015

Warm air easing over the cold ground resulted in a soft silvery fog today as John and I went for our second tree survey for the season. John looks for any sign of buds swelling on trees near the big oak, foreground, that I am studying at the Harvard Forest for my book, Witness Tree.

Snow eating fog swaddles the forest today. A phenomenon of warm air riding over the cold ground and snow, the fog wraps the trees in ghostly white, and silently erases the snow with its warm breath.

But there is still plenty of snow left. Out today for a second tree survey of the new year, I measured snow a foot deep in lots of places. But for the first time, entire features of the landscape I hadn’t seen in months returned.

John O’Keefe, field phenologist for the Harvard Forest, began his spring tree survey this month. Every week until mid-June, he will walk a path through the same 50 trees he has watched go through their seasonal progression for 25 years. The result, as he makes notes, is a richly detailed record revealing the shifts in phenology, or seasonal timing in the era of global climate change. The variability year to year is dramatic, with the earliest spring on record just five years ago, while this may turn out to be the latest.

Rain today beautifully brought out the colors and texture in the bark of the big oak I am studying at the Harvard Forest.

We record the appearance of the trees as they bud and leaf, and whole lot more. I was struck today by the return of the landscape itself. The stonewalls are back. They had been missing from view for months, the colors lost to white, the shapes to deep drifts, humped like sleeping animals. The big surprise was the barrier of big boulders across a wagon road that I had been walking right over all winter, without even knowing it. The snow was that deep.

I walked right over this barrier of boulders all winter without even knowing it was there until today. It’s good to see the landscape again as the snow melts, especially the beautiful stone walls.

The physical changes we saw in the woods today, compared with last week, were dramatic. It’s always that way:I think there can’t be that much to experience that’s different in just one week, and then there is. The sounds of running water, deep puddles, mud, and the return of bare ground in some spots – leaves at last. Even the scent of the air has changed; it is full of the smell of earth and decomposition. But today in 50 trees we still saw only one bud – one! – with a tuft of leaves emerging, on a red elderberry. But it was a beautiful bud, fat, green, and alive. One striped maple showed cracks in its buds, and a few red maples showed a bit of swelling. That’s it.

But the vernal pool at the Hemlock Hollow was transformed with the first edges of open water. Drops of rainwater from the hemlock boughs overhead made silvery rings in the still water. It won’t be long now until the wood frogs emerge, and begin their urgent quacking chorus.

Open water in the vernal pool at Hemlock Hollow will soon draw chorusing wood frogs. Maybe even tonight if we have more warm rain.

I have my window open in the office as I write this, and the fragrance of spring keeps finding me. The movement of fog in the warm air as I look out to the forest is beautiful, winding through the trees. It is a day of gentle transition, full of promise. “Not a lot of change biologically,” John said as we headed back in to Shaler Hall from our walk. “But there’s a sense of a lot of change coming.”

ODE TO HEMLOCK

April 9, 2015

As I look around me, I cannot believe these grand trees, reigning supreme here for 8,000 years, are being taken out by a tiny bug, no bigger than a pencil point. But it is true: the hemlocks are dying.

The Hemlock Hollow is a special place to me in the Harvard Forest. The sun lights its fresh green canopy year round, brightening the somber palette of winter. By May, as the humidity starts to cling close, walking into the Hemlock Hollow, as we call this green glade, is pure refreshment; it feels ten degrees cooler in here. The softness of the needles underfoot is distinct. Slow to decompose, the needle litter builds up, getting softer and thicker year upon year. Piled many inches deep, it feels plush and springy as a mattress. It was the Hemlock Hollow that convinced me to switch from hiking boots to thin-soled shoes for my forest walks, so I could savor the many different textures and depths of the forest floor – and especially the deluxe cushy carpet of the Hemlock Hollow.

Hemlocks dominate their realm, shading out plants in the understory. The result is a park-like grove uniquely pleasant for walking.

The Hemlock Hollow, like any hemlock grove, is also an ecologically distinct and special place. Because the canopy captures nearly all of the sun’s light, the forest floor is a place of rare sun flecks where only the most shade tolerant plants can eke out a living. The result is a park-like grove, with clear sight lines across the understory beneath a nearly sealed canopy. It’s part of the unique feeling of being in this part of the forest, with a sense of both aspect and refuge.

There is a special quality to the light and presence of this part of the forest that no photo seems entirely to capture. Year-round, the hemlocks’ feathery, soft, flexible needles and branches that begin low on their trunks interlace to create a canopy that locks the understory into deep, velvety shade.

The ability of hemlock boughs to trap snow provides refuge from deep drifts that are important to wildlife, especially deer.

Hemlocks dominate their realm. Monarchs of shade, they set the temperature, the water regime, the soil chemistry and determine the suite of life that will share their domain. The Hemlock Hollow is a place of quiet things: salamanders on their earnest travels, a vernal pool that draws wood frogs for their urgent errand to breed in early spring, then dispersing as mysteriously as they arrived.

As Harvard Forest researchers so engagingly write in their book, Hemlock, A Forest Giant on the Edge, in this particular grove, for some 8,000 years, hemlock have made the rules. They have flourished here in a triumphant return after mysteriously dying out, the pollen record shows, some 5,500 years ago. Hemlock then recovered almost completely, after a period of regional scarcity that lasted 1,500 years. Poignantly, hemlock regained their reign only to now once again face mortal threat.

First reported in the US in Virginia 1951, hemlock woolly adelgid is a small, aphid-like insect on the march. In New England, it attacks and gradually kills eastern hemlock by draining their vital juices through a small sucking mouthpart. Even a large healthy hemlock can be killed in ten years. Already millions of hemlocks have been infested, from Georgia to southeastern Maine, and in the Harvard Forest, too, the hemlocks are already dying by degrees. There is more sun here now than there should be, more open sky, too many needles on the snow in winter. In spring, instead of a season of robust fresh growth, there is a death rattle of needles raining to ground.

Hemlock wooly adelgid can kill a healthy hemlock in less than ten years. This hemlock at the Harvard Forest was healthy five years ago. Photo by David Orwig.

David Orwig, a senior forest ecologist at the Harvard Forest studies the effects of the adelgid at the forest and throughout southern New England. He came in from a walk in the forest today with a few springs of hemlock in his pocket. Climate change has helped adelgid advance in their range further and further north. The discouraging thing is that even after a cold winter just passed with some days of temperatures dipping below zero, the adelgid are still thriving. He pulled a branch from his pocket and flipped it over to show me: It was covered with the telltale white cottony casings of adelgid that will soon begin laying eggs, reproducing not once, but twice in a season. The insects don’t have wings, but instead are carried on the wind, from tree to tree.

David Orwig, a senior ecologist at the Harvard Forest, back from a walk today surveying the Hemlock Hollow. Orwig holds a sprig of hemlock in his hand — and another in his pocket.

In a forest, there is no practical defense against the adelgid’s incessant spread. So instead, at the forest the approach is to study the demise of a tree that so dominates its realm. What happens to the forest? To the stream flows, the animals and understory plants? To learn how the forest will respond as hemlock wooly adelgid take their toll, researchers in 2005 girdled every hemlock in a long-term ecological research plot. They have since been watching these hemlock die, and counting the stems of the trees that come back to take their place, to understand what forests of the future here might look like. A companion plot was commercially logged, to see the difference in response between the gradual death inflicted by the bug, compared with the more familiar response to a commercial–style harvest. I walked the ghostly girdled trees in the hemlock removal experiment with Audrey Barker Plotkin, a senior research scientist at the Harvard Forest one afternoon last autumn, chalking every stem as we counted it. It seemed the only thing I recorded was black birch in a thick forest of new young trees springing up under the grey visage of the dead hemlocks. Hemlock’s loss, at least at this point, is looking like black birch’s gain.

Hemlock woolly adelgid — the white dots –infest this hemlock twig Dave Orwig brought back from the Harvard Forest today. The long cold winter hasn’t slowed down the invasive pest.

After these hemlocks fall, this will still be a forest. But it won’t be the forest I have come to know and love; that special cool refuge on hot days, quiet and deliciously dim, like an air-conditioned library with the shades drawn. And what of the refuge it provides in winter for animals – for deer seeking respite from deep snows, the porcupine seeking a resting spot in its dense branches, or a tasty snack of its nutritious branch tips?

I recently visited the Hemlock Hollow, to enjoy its winter beauty, and the quiet swoosh of its boughs, like the sound of a seashell cupped to the ear. It won’t be the same here in winter, with sun streaming through the canopy of deciduous trees that will move in after the hemlocks are gone. And so this bit of forest now so special, unto itself, will look like the forest everywhere else. A bit of diversity of the native New England wood will be gone. A deep bass note will be lost in a symphony that has played for 8,000 years.

Penning notes for this post on a recent winter afternoon, while sitting on a log at the Hemlock Hollow. I will miss hemlock.

A NEW WORLD EMERGES

April 7, 2015

The big melt is underway. Heading out to the big oak I am studying at the Harvard Forest this year I saw lots of something I haven’t seen since Thanksgiving: bare ground.

After months and months of solid snow cover all the way up to last week, the ground is emerging. The streams are running. The air smells of earth. The mornings have changed – not only in their light, but in their sound. The birds are back. So are the chipmunks and the squirrels. Even the first bugs. I saw a wooly bear caterpillar saunter across the ground a few days ago.

As the snow melts, secrets of winter are revealed. How lovely to spot the subnivian tunnels used by the small mammals all winter to get to their food caches and to fresh water. There is a stream that runs behind my house and when I looked out the window this morning I saw the tracery of tunnels to water built by animals all winter, revealed as the top layers of snow finally melted away.

How beautiful to see the animals’ subnivian tunnels revealed as the snow melts away. These lead to the stream outside my house, the source of fresh water for many tiny lives all winter.

How busy it was under that perfect white covering all winter. Not only the infrastructure thrumming with travel all winter long, but the food caches! All around the base of the big oak were split acorns and the devoured feasts of a long winter. What seemed like a quiet frozen world was actually abuzz non-stop, under the snow. Those little holes I saw at the snow surface led to busy tunnels and delectable larders.

What feasting has been going on under the snow all winter! These acorns were from a meal under the big oak I am studying at the Harvard Forest. I finally saw bare ground — and this squirrel midden — for the forest time today as the snow eases back from its trunk, revealing a winter’s worth of meals.

And there was another surprise, too. Last May, I came out to the Harvard Forest to move some things into the basement of my house to use when I returned to start my Bullard fellowship in the fall. And I brought a secret: an oak tree I had sprouted in a pot that spring, from acorns I gathered in the forest. I tucked it in by the pasture fence behind the house, wished it luck, and headed back to Seattle for the summer to go back to work at my usual job as a reporter in the newsroom at the Seattle Times.

When I returned to the forest in the fall to begin my fellowship, the very first place I went was the fence – where was the tree? How had it fared? But so many wildflowers had grown up in the area, I couldn’t find it. Had it been mowed? Was it gone? I couldn’t tell.

Emerged from the winterkilled meadow and three feet of snow as winter relents: the oak I planted last year, raised on my windowsill from an acorn. I was so glad to see it had survived.

Today, as I scouted out the animal tunnels, I noticed the winterkill had leveled the wildflowers and weeds. I wondered if…I looked long enough – could it be there? Sure enough. Bravely grown to calf height, with new buds set for a new year: the little oak.

Emerged from the snow, and growing strong. Just a week ago it seemed spring would never come. Now its welcome signs are everywhere.

A TALE OF TWO SPRINGS

April 2, 2015

Five years ago the Northeast saw its earliest spring on record; will this year be the latest?

John O’Keefe, field phenologist at the Harvard Forest and I went out on John’s first tree survey of the new year today. While it was April 1 – his traditional first walk of the season – we were not intending it to be an April Fool’s gag. But you could have thought so, as we post-holed through the snow. There was surely no spring to be had! Not in the trees, not in the shrubs, the birds, or the animals. Just a bit of open water here and there, a very few patches bare ground, and the streams were running. Other than that, it sure looked a lot like…winter.

The first bud test of the new year. We saw virtually no signs of spring yet at the Harvard Forest on our first phenology walk of the year. John’s records show at this time in 2010, there was no snow at all, frogs were singing, and red maples were in flower. Photo by Doug MacDonald

I packed a ruler along and we measured at least 10 inches of snow on the ground in most places. The Hemlock Hollow, the vernal pool we watch where the wood frogs first sing, was still sealed over with ice. The day was sunny but cold, in the high thirties. And the trees – well. John has been surveying the same 50 trees for 25 years to track their seasonal progression. The trees’ first green up marks the beginning of the photosynthetic cycle for the year – and he closely notes the changes in the trees, from first swelling and cracking of buds to leaf emergence, growth, color and drop.

A squirrel scooting over the snow is photographed by the wildlife camera set up by the big oak I am studying at the Harvard Forest. This is a tough time of year for animals running out of food stores while snow is still deep on the ground.

John makes his observations in collaboration with the Andrew Richardson, associate professor at Harvard University, who uses the seasonal progression of the canopy as a marker of the effects of climate change on the forest. Over the past 25 years, O’Keefe has noted a shift toward earlier on average springs, later falls, and winter squeezed on both ends because of global warming.

But this year’s spring is so late, and last year’s too, that the average earlier spring trend could even be reversed, and will surely be dampened, John said. Because fall has been consistently later, the overall longer growing seasons of recent years will still likely still hold true.

We checked for any sign of spring in the trees and saw just maybe a little slight perhaps sort of tiny bit of swelling on the buds of a few black cherry trees – always among the first to transition. Nothing else had budged a bit. The snow shone brilliantly in the spring sun, but the sun’s higher position in the sky was about it for seasonal change.

We came across a few smaller sample trees buried nearly to their flagging in snow. I nearly lost the ruler while making a few measurements, the snow banks were so deep. At least the streams were thawed and moving.

Once back at Shaler Hall, we were curious to see John’s data from the earliest spring in his 25 years of record keeping, walking the same 2.5 mile loop and examining the same trees on April 1, 2010. We knocked the snow off of our boots and went down to his office to pull the data.

What a shocker. April 1, 2010 was booming. The wood frogs were singing at the Hemlock Hollow. The skunk cabbage was “still blooming.” The red maple flowers were open. The striped maple’s bud scales were split, and witch hazel buds were softening. The was no ice on the Hemlock Hollow, no snow anywhere, and red oak acorns on the wagon road were germinating. The mayflower was up, and it was nearly 60 degrees. It had been warm for weeks, with late February and March consistently warmer than normal.

It was interesting to pull John’s record from the same day five years ago and see just how different the earliest spring looked from the same day in what may turn out to be the latest.

This is what scientists mean when they talk about inter-annual variability. Big swings, from one year to the next, as global change rattles the seasonal works. Who knows what next year will bring? These past five years tell us this much: anything could happen.

Any spring up there? John uses binoculars to look for any signs of swelling on the buds of the big red oak I am studying at the Harvard Forest. It’s going to be a while. The camera beaming photos every half hour during daylight hours of the big oak to the Harvard Forest home page is visible on its mount in the snow, to the right of the tree.

HISTORY WRITTEN IN WOOD

March 27, 2015

Mute only in words, trees speak volumes to people like David Orwig, a senior ecologist at the Harvard Forest and master of reading landscape history in the rings of trees.

Forest Ecologist Dave Orwig hunting history in the core of BT QURU 03, the 100-year old oak I am studying here at the Harvard Forest

Trees are living timelines. Droughts, wet spells, fires, insect outbreaks, hurricanes, ice storms: they are all written in wood. Rings of annual tree growth, showing light in spring, and dark in summer, record the years of a tree’s life. Suppressed rings mean something stalled the tree’s growth – an event, a neighbor, some changed condition in its environment. Then a big spurt of growth – called a release – narrates the tree bursting free to grow robustly. Rain fell, a big tree nearby crashed over. Something somehow set it loose.

Put together with other records, tree rings, read correctly can be powerful and reliable narrators of history, with an error bar of zero. Here at the Harvard Forest, researchers often combine the extensive land use records in the Harvard Forest Archives with tree ring interpretation to see amazingly fine detail of landscape history.

While here at the forest as a Bullard Fellow I am writing a book about the life of single 100-year old red oak. I’m using all kinds of records and documents in my research, in addition to observations of the tree and the forest to tell its story. I’ve also dug into the Harvard Forest Archives – and watched Orwig core the tree last June to confirm its age. I keep its cores right here on my desk all the time, a touchstone to the tree’s inner life over the years.

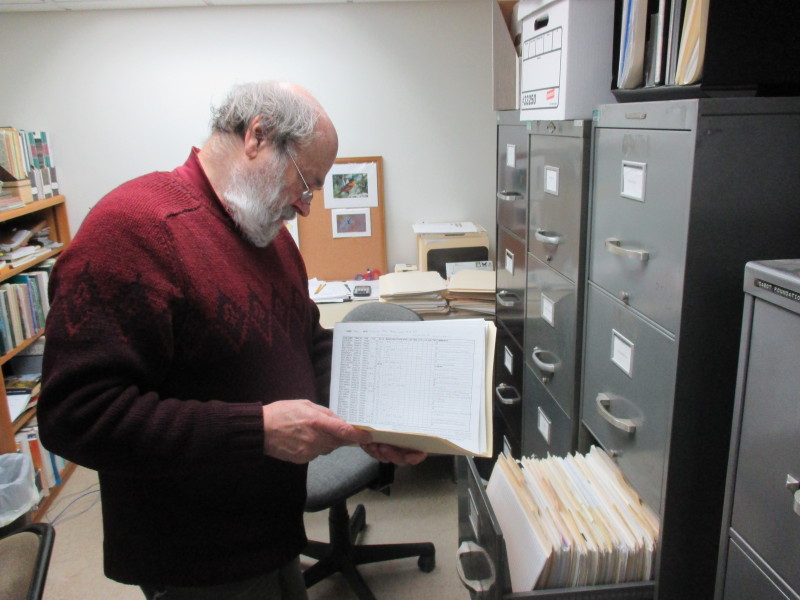

This morning, Orwig had some surprising news: he had stumbled across a bit of the oak’s history in the archives in some research of his own. He was reading stand records from another area of the forest, and came across notes about a big gypsy moth attack in 1944. The hand-written field notes in the archives tell a richly textured story of the life of the forest and people who have worked with it since the forest was founded in 1907. Thinning, harvesting, surveying, planting, mapping, records of big storms, fire, and other disturbances – foresters and researchers over the years seem to have recorded just about everything.

Over the years foresters and researchers have recorded a rich trove of landscape history, preserved in the Harvard Forest Archives.

The records have been carefully indexed and curated, and many are even digitally scanned for anyone’s use, for free, online. As Orwig read about that gypsy moth attack, something clicked — a memory of the core he pulled from the oak last summer.

“Do you still have that core?” Orwig asked, stopping by at Shaler Hall this morning. We looked at the core together under the microscope in his office, and sure enough, the core bore out his hunch. A strong grower in nearly every year of its history, the oak’s fat, evenly-spaced growth rings march through time. But then there it was, written in wood: a squeeze in the summer growth of the oak in 1945. The gypsy moth attack of 1944.

The gypsy moth attack of 1944 is recorded in the suppressed latewood, or summer growth of the oak I am studying, visible in the narrower dark band of the 1945 tree ring just to the left of the crack in the core. Cores are sometimes cracked when pulled from a tree, but can still be read when glued and mounted for study, as this one is.

The insects typically build up over several years, doing cumulative damage to the robustness of trees, and can even kill them. In this case the oak was suppressed just one year, then bounded back.

How exciting to see people and trees each recording history in their own languages, for us to discover all these years later.